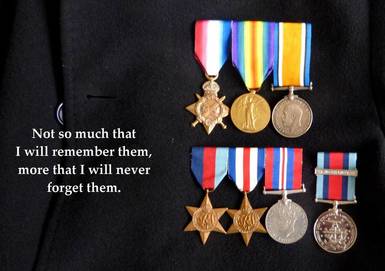

Read below, this powerful poetic reminder of how we fail to honour our debt to those who sacrificed all, their health, their sanity, their homes and families . . . their lives. Here is the eternal truth of their glory matched by our shame.

The Last of the Light Brigade

There were thirty million English who talked of England's might,

There were twenty broken troopers who lacked a bed for the night.

They had neither food nor money, they had neither service nor trade;

They were only shiftless soldiers, the last of the Light Brigade.

They felt that life was fleeting; they knew not that art was long,

That though they were dying of famine, they lived in deathless song.

They asked for a little money to keep the wolf from the door;

And the thirty million English sent twenty pounds and four !

They laid their heads together that were scarred and lined and grey;

Keen were the Russian sabres, but want was keener than they;

And an old Troop-Sergeant muttered, "Let us go to the man who writes

The things on Balaclava the kiddies at school recites."

They went without bands or colours, a regiment ten-file strong,

To look for the Master-singer who had crowned them all in his song;

And, waiting his servant's order, by the garden gate they stayed,

A desolate little cluster, the last of the Light Brigade.

They strove to stand to attention, to straighten the toil-bowed back;

They drilled on an empty stomach, the loose-knit files fell slack;

With stooping of weary shoulders, in garments tattered and frayed,

They shambled into his presence, the last of the Light Brigade.

The old Troop-Sergeant was spokesman, and "Beggin' your pardon," he said,

"You wrote o' the Light Brigade, sir. Here's all that isn't dead.

An' it's all come true what you wrote, sir, regardin' the mouth of hell;

For we're all of us nigh to the workhouse, an' we thought we'd call an' tell.

"No, thank you, we don't want food, sir; but couldn't you take an' write

A sort of 'to be continued' and 'see next page' o' the fight?

We think that someone has blundered, an' couldn't you tell 'em how?

You wrote we were heroes once, sir. Please, write we are starving now."

The poor little army departed, limping and lean and forlorn.

And the heart of the Master-singer grew hot with "the scorn of scorn."

And he wrote for them wonderful verses that swept the land like flame,

Till the fatted souls of the English were scourged with the thing called Shame.

They sent a cheque to the felon that sprang from an Irish bog;

They healed the spavined cab-horse; they housed the homeless dog;

And they sent (you may call me a liar), when felon and beast were paid,

A cheque, for enough to live on, to the last of the Light Brigade.

O thirty million English that babble of England's might,

Behold there are twenty heroes who lack their food to-night;

Our children's children are lisping to "honour the charge they made - "

And we leave to the streets and the workhouse the charge of the Light Brigade!

I regret I have no name of the poet in order to credit and honour them.

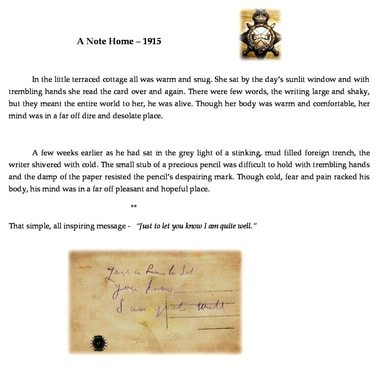

“I am well.”

(Winter, 1915, the Somme.)

In her cottage, warm and snug,

she reads the card again.

With trembling hands around hot mug,

she senses far off pain.

**

In stinking, mud filled, foreign trench,

he writes her one last card,

and shudders in the cold and stench,

of freedom, won so hard.

**

(Winter, 1915, the Somme.)

In her cottage, warm and snug,

she reads the card again.

With trembling hands around hot mug,

she senses far off pain.

**

In stinking, mud filled, foreign trench,

he writes her one last card,

and shudders in the cold and stench,

of freedom, won so hard.

**

The War to end all wars –

and for so many, it was just that.

Are we as sad, as he once was,

to see his friends all killed,

to sing the hymns and utter prayers

as grave on grave was filled.

In trenches foreign, far from home,

he laboured night and day.

And with the gas came nightmares,

he wished could go away.

But very rarely, leave it came,

to home, and part this strife,

for new mown hay and roses

and marry, his new wife.

By special licence they were wed,

dismay is theirs to bear.

The telegram it said quite clear,

‘Recall to duty, there.’

A farewell hug, a kiss goodbye,

so sad to go away.

But duty calls, to send our friend

once more into the fray.

Back, where blood of man and horse,

flowed red into the ground,

all through that mud they marched as one,

until their peace was found.

and for so many, it was just that.

Are we as sad, as he once was,

to see his friends all killed,

to sing the hymns and utter prayers

as grave on grave was filled.

In trenches foreign, far from home,

he laboured night and day.

And with the gas came nightmares,

he wished could go away.

But very rarely, leave it came,

to home, and part this strife,

for new mown hay and roses

and marry, his new wife.

By special licence they were wed,

dismay is theirs to bear.

The telegram it said quite clear,

‘Recall to duty, there.’

A farewell hug, a kiss goodbye,

so sad to go away.

But duty calls, to send our friend

once more into the fray.

Back, where blood of man and horse,

flowed red into the ground,

all through that mud they marched as one,

until their peace was found.

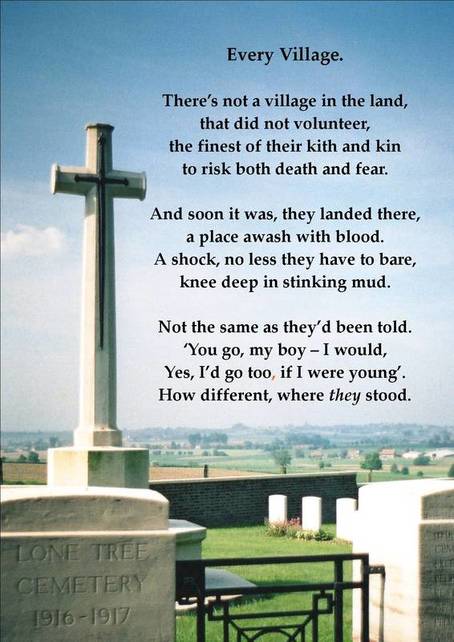

In Every Place. . .

In every place, there was a face,

remembered with a tear.

And evil laughed, when sword it drew,

for those who lived in fear.

Their sons had gone, and answered call

to arms and fight the foe,

while back at home, far from the front,

how could their mothers know?

They only knew, when it was sent,

sad letter from the King.

Cheap telegram, it told of loss;

their son; it could not bring.

No place to grieve, their son, no grave,

such loss they could not hide.

They knew not how, or when, or why.

Was it general’s pride?

Long years they pass, and few are left,

Lost souls, now carved in stone.

With poppies red, we still do mourn,

for nothing can atone.

In every place, there was a face,

remembered with a tear.

And evil laughed, when sword it drew,

for those who lived in fear.

Their sons had gone, and answered call

to arms and fight the foe,

while back at home, far from the front,

how could their mothers know?

They only knew, when it was sent,

sad letter from the King.

Cheap telegram, it told of loss;

their son; it could not bring.

No place to grieve, their son, no grave,

such loss they could not hide.

They knew not how, or when, or why.

Was it general’s pride?

Long years they pass, and few are left,

Lost souls, now carved in stone.

With poppies red, we still do mourn,

for nothing can atone.

The poppies

They went to war when they were boys

They didn't really have a choice

They marched away and looked so brave

While mothers and sweethearts smiled and waved

Was it Cyril or Tom or Bert

Who left to fight, they'd not get hurt

They were sent to Belgium and France,

They didn't really stand a chance

So patriotic & filled with pride

But within each regiment, young men died

A bright red poppy, became the sign

For remembrance of that time

This year, ceramic ones were made

Each one unique, and people paid

To raise money and honour the men

Who were never seen again

And now each poppy, crafted by hand

Is displayed at the Tower for people to stand

and look in awe, & some shed tears

For what was lost during those years

In the moat, a sea of red

Not blood this time, though men are dead

Eight hundred thousand and more were lost

So many lives and such a cost

One poppy, one man, so many died

Who was your link, your family's pride

Angela N.

A war to end all wars ... that was their hope . . .

how could it be otherwise, they thought.

how could it be otherwise, they thought.

For they who gave their youth,

their health, their lives,

what's a few moments of ours

to think on them?

"And soon it was that we were home, a lantern at the door,

and in we came with smile and cheer

and everybody waiting here,

as they had been before."

Poem by Sue Valentine.

Here is a true story of one man's life in the Somme during the first world war.

One man's journey as a surviving sapper of the Great War 1914 - 1919.

Fact based story from War Diaries maintained at Kew Records Office, London..

and in we came with smile and cheer

and everybody waiting here,

as they had been before."

Poem by Sue Valentine.

Here is a true story of one man's life in the Somme during the first world war.

One man's journey as a surviving sapper of the Great War 1914 - 1919.

Fact based story from War Diaries maintained at Kew Records Office, London..

We shouldn't just remember on poppy day and so I want to share with you a youtube link (opens in a new window), to a powerful anti war song by Eric Bogle, it is sung by a lady (of Klonakilty) with great feeling, the song is often called The Green Fields of France or Willie McBride. Surely no one can walk those fields and the war graves and not be affected deeply. I followed the footsteps of my own grandfather who was there from 1914 to 1919. He was lucky, if you can call it that, for thousands are still there waiting to be found. You won't be sorry if you take a few moments to listen to the song, a combination of words, music and passion The green fields of France.

********************

Thomas Edwin Baker of Morwenstow Cornwall, remembered.

Untimely death in The Crimea.

Thomas Edwin Baker of Morwenstow Cornwall, remembered.

Untimely death in The Crimea.

In search of a better life and in service to Queen and Country, young Thomas Baker was to leave his loving family and home in Morwenstow, Cornwall for the war torn shores of Crimea; a journey for him that will last an eternity for he as yet to come home.

Enlisted as a soldier in the Scots Fusilier Guards, he was to die at Sebastopol; in all probability stricken down by the Cholera, as were so many at that time. He was 23 years of age, his name was Thomas Edwin Baker.

This page is about his true story and by implication for all those young people that make such ultimate sacrifice.

******************

This song, which you can play by using the controls below, was sung by Ian Hudson and friends. This centuries old song appears in many different guises and various titles but it's essence is that of a young man who enlists and must leave his sweetheart in hope that he will return to marry. This emotive song helped inspire me to write the story of Thomas, a man who was much loved by his parents, who placed a memorial stone in Morwenstow churchyard next to their own plots: his body would never return. . . . but perhaps his spirit did.

Here is the full, true story as published in the book

"I want to tell you a story" by Richard Small

*******

“I be Thomas,” he said, “and so very far from home”

“I be Thomas, sir. I be Cornishman Thomas Edwin Baker of Morwenstow, and in truth I do know I'll not be seeing home nor kin again.

If you have but a little time to share I'd tell you of my tale. ..........

I be only 23, sir, and the winter cold has numbed my hunger gnawed bones in this God forsaken place, and the light, sir, begins to fade as I lie here in these once proud rags. .......

Pray, stay a while, before the light dims altogether. .........

I am the youngest living of eleven born to my dear mother Grace, sir, and we all lived at Cory, a 15th century farm of some 64 acres, an easy mile or so from the church and close by the Cornish north west coast. Even they farmers be poor these days, sir, the county is in decline and my good father Richard Baker, he needs must also work as clerk to the parish ...... I reckon since before I was born. I be the second Thomas in the family sir, my late brother Thomas died in Exeter age seventeen, two years afore I be born. We’m named after our grandfather sir, so we be.

I be used to life and death, sir, being brought up on a farm and all that .. and many a ship wreck would leave her dead on the shore below....... the worst I recall was when I was eleven years of age ... seven corpses carried from the beach to lay by the lych gate .... many of the parish turned out to help .. a grand ship, the Caledonia of Arbroath, she came aground and was lost at Sharpnose Point in a terrible September nor' easterly gale, .... they be cliffs there sir, 300 feet sheer down to merciless ragged rocks and that wild Atlantic. The tide and long-shore drift would carry the bodies north along the coast to where the living could just find a way down to meet the dead, sir. Swollen drowned and rock battered by surf they be as they lay silent awaiting burial at St Morwenna's by our vicar; a strange man indeed he was, so my father tells me, the Reverend Hawker was his name and strange indeed ..... but he be good of heart enough to give Christian burial to they strangers, sir. Ar he did be strange though sir, why, he smoked the Opium and spent his days staring out to sea. …….. The gravedigger earned his shilling that day for sure.

They be a hardy lot at Morwenstow, sir, some say wreckers and smugglers all, but not all sir, not all. Mind you, sir, if you can keep a secret, twas said that a floor at Cory once collapsed to reveal a cavern down below ... no doubt for some past use that few dare speak of. ........ Those years were hard, sir, except for the sea given bounty from soul lost ships wrecked nearby, and there were a few. Many a cottage or barn has a ship’s timber at its heart. I remember well as a child two or three ships going down … and that be only they close to home, there were plenty more …. A deadly coast for sailors sir.

The county towns were filthy places sir, and disease no stranger to their folk. Why, sewage lay in the streets sir, and mostly people starving, .... the 'hungry forties' I heard it called, and that they were sir......... why, later on, when the regiment was posted in Cork, we saw the ravaging toll of hunger follow a potato disease that killed the harvest year on year, the Irish died in their thousands sir..... 'twas terrible indeed sir. They that could, emigrated, like so many did the Cornish, in their droves sir, only the new world offered any chance of life.

By the time I was seventeen sir, I had become a tailor, just like my older brother Henry, it was a poor way to turn a penny sir, but a necessity of the day ...... disease had struck the county sir, and west Cornwall in the grip of cholera. By the time I was eighteen smallpox was rife ... the misery seemed endless. What chance does a young man have, ... to find a home, a sweetheart, a wife, and work ... it all seemed so hopeless.

Then, one day, I be on an errand towards the moors when some fine men came across my path. Well fed they be and tall and strong sir, all dressed in bright red uniforms .... 'You lad, yes you', shouts the recruiting sergeant at me, 'come join us in service to her majesty Queen Victoria, come join us in adventure'. To the beat of their drum sir I did step forward ..... it was the 18th of May 1850 sir, they gave me a number ..... 3993 it be sir .... and a promise of a living as I signed my name where the sergeant pointed. Oh, how I recall my heart racing as I hurried back home to Cory to tell my father that his youngest son was a tailor no more but an honourable soldier in the Queen's favourites, the Scots Fusilier Guards.

My dear mother was afraid for me and afeared to lose her youngest son, but I do believe my father was proud of me and could see that I may find a better life this way.

.......... Are you still there sir? ....... I cannot see much any more .... it must be getting dark and the orderlies not yet lit the lamps.

I was at Alma sir, aye and at Inkerman too, such bloody fighting ….. the smell of gunpowder, blood and fear, …….twas fearsome desperate fighting sir, …. At Inkerman we were outnumbered, though we didn’t know it in the fog, …… fog so thick we didn’t know who was friend or foe till we saw their faces and bayonets …. Murderous times sir, … I can hear the screams now …

Twas September last we set siege to Sebastopol, four miserable winter months ago, a November storm sank our ships that carried the where with all to see us through, and now us have precious little to comfort. ........... did you know sir, they made me sergeant, and I be only a young man too. Not that you can see the stripes on my rags of uniform now ....... oh so different just one year ago when we marched past Buckingham palace and our gracious Queen Victoria, we marched tall and proud, oh how bright the colours in the late winter sun, the heavy rhythmic crump of black boots on gravel, flags a flying, officers a shouting, the band, the crowd … our Queen … we felt on top of the world sir … invincible we were. ....... oh, how so much has changed now sir, many a good friend has gone before me, George Ramsey, blacksmith, died just a few days ago ... same as I have got I reckons, ..... and good old Daniel Brown, another tailor like I he was sir, he was killed first day at Inkerman along with some hundred and seventy other good souls....... we lost the same at Alma sir...... tis a bloody business this war with the Russians but our worst enemy is nature herself by far. All we are sir, grocers, weavers, tailors, labourers and carpenters, brought to a foreign land as soldiers to die in disease hunger and cold.

Tis the men killed by Russian shot or bayonet that be the lucky ones. Theirs is pain no more, yet history will mark their sacrifice with honour sir, ..... what of us sir, who merely died a death we could have had at home sir, as many a good Cornishman has, …. are we not all comrades in arms sir, are we not all children of our country ….. are you still there sir, I fear I fall to a weary deep sleep …… I would my dear mother was near … please remember me sir, … I be Thomas Edwin Baker and so very far from home …. Du re bo genen ni oll ……..”

**

So spoke Thomas Baker one warm spring day as I brushed grass cuttings from his marker in the graveyard at Morwenstow.

Perhaps, should you stand and listen he'll 'speak' to you too.

For one, I’ll not forget him.

**

In the above story all the facts are as historians have recorded,

by poetic licence, his spoken words are mine; perhaps, if I were in his shoes, my words would be his too.

Ships lost on Morwenstow rocks for the relevant period.

Caledonia 1842

Phoenix 1843

Eliza 1846

Thomas Edwin Baker was baptised 29th October 1831

Enlisted in Scots Fusilier Guards on 18th May 1850 and died 16th January 1855

The old farm house at Cory burned to the ground in the late 1800s.

Richard Baker buried 13.3.1860 residing at Gooseham age 73.

Grace Baker buried 8.3.1863 residing at Cory

Reverend Robert Stephen Hawker was vicar at Morwenstow from 1834 for 41 years.

In 1854 the Scots Fusilier Guards sailed from Cork to start their journey to the Black Sea.

23rd February 1854 they paraded at Buckingham Palace in front of Queen Victoria.

They landed in the Crimea in September 1854 after first being deployed in Malta, Bulgaria and Turkey.

Thomas was entitled to the Crimea medal with clasps for Alma, Inkerman and Sebastopol. A medal he would never see.

14th November 1854 a great storm sank the British ships carrying winter provisions.

At Alma on 20th September 1854 the Scots Fusilier Guards lost 11 officers and 149 men; at Inkerman 5th November 1854 they lost 9 officers and 168 men (half their strength)

George and Daniel were indeed soldiers with Thomas.

Summer in the Crimea can be 30 degrees C. Winter can drop below freezing.

1849 cholera struck west Cornwall. 1849 – 1850 smallpox epidemic.

Where is Thomas buried? Some unknown grave in the East that is forever England; he likely died of disease; cholera was a big problem and can at times kill in only a few hours. If he had been transferred to the converted barracks at Scutari in Istanbul, Turkey it would have been recorded and it isn’t. Scutari was where Florence Nightingale did her pioneering work … which sadly was often ignored by the powers of the day. 6,000 died of cholera at Scutari.

‘Du re bo genen ni oll’ Cornish for ‘May God be with us all’

*********

"I want to tell you a story" by Richard Small

*******

“I be Thomas,” he said, “and so very far from home”

“I be Thomas, sir. I be Cornishman Thomas Edwin Baker of Morwenstow, and in truth I do know I'll not be seeing home nor kin again.

If you have but a little time to share I'd tell you of my tale. ..........

I be only 23, sir, and the winter cold has numbed my hunger gnawed bones in this God forsaken place, and the light, sir, begins to fade as I lie here in these once proud rags. .......

Pray, stay a while, before the light dims altogether. .........

I am the youngest living of eleven born to my dear mother Grace, sir, and we all lived at Cory, a 15th century farm of some 64 acres, an easy mile or so from the church and close by the Cornish north west coast. Even they farmers be poor these days, sir, the county is in decline and my good father Richard Baker, he needs must also work as clerk to the parish ...... I reckon since before I was born. I be the second Thomas in the family sir, my late brother Thomas died in Exeter age seventeen, two years afore I be born. We’m named after our grandfather sir, so we be.

I be used to life and death, sir, being brought up on a farm and all that .. and many a ship wreck would leave her dead on the shore below....... the worst I recall was when I was eleven years of age ... seven corpses carried from the beach to lay by the lych gate .... many of the parish turned out to help .. a grand ship, the Caledonia of Arbroath, she came aground and was lost at Sharpnose Point in a terrible September nor' easterly gale, .... they be cliffs there sir, 300 feet sheer down to merciless ragged rocks and that wild Atlantic. The tide and long-shore drift would carry the bodies north along the coast to where the living could just find a way down to meet the dead, sir. Swollen drowned and rock battered by surf they be as they lay silent awaiting burial at St Morwenna's by our vicar; a strange man indeed he was, so my father tells me, the Reverend Hawker was his name and strange indeed ..... but he be good of heart enough to give Christian burial to they strangers, sir. Ar he did be strange though sir, why, he smoked the Opium and spent his days staring out to sea. …….. The gravedigger earned his shilling that day for sure.

They be a hardy lot at Morwenstow, sir, some say wreckers and smugglers all, but not all sir, not all. Mind you, sir, if you can keep a secret, twas said that a floor at Cory once collapsed to reveal a cavern down below ... no doubt for some past use that few dare speak of. ........ Those years were hard, sir, except for the sea given bounty from soul lost ships wrecked nearby, and there were a few. Many a cottage or barn has a ship’s timber at its heart. I remember well as a child two or three ships going down … and that be only they close to home, there were plenty more …. A deadly coast for sailors sir.

The county towns were filthy places sir, and disease no stranger to their folk. Why, sewage lay in the streets sir, and mostly people starving, .... the 'hungry forties' I heard it called, and that they were sir......... why, later on, when the regiment was posted in Cork, we saw the ravaging toll of hunger follow a potato disease that killed the harvest year on year, the Irish died in their thousands sir..... 'twas terrible indeed sir. They that could, emigrated, like so many did the Cornish, in their droves sir, only the new world offered any chance of life.

By the time I was seventeen sir, I had become a tailor, just like my older brother Henry, it was a poor way to turn a penny sir, but a necessity of the day ...... disease had struck the county sir, and west Cornwall in the grip of cholera. By the time I was eighteen smallpox was rife ... the misery seemed endless. What chance does a young man have, ... to find a home, a sweetheart, a wife, and work ... it all seemed so hopeless.

Then, one day, I be on an errand towards the moors when some fine men came across my path. Well fed they be and tall and strong sir, all dressed in bright red uniforms .... 'You lad, yes you', shouts the recruiting sergeant at me, 'come join us in service to her majesty Queen Victoria, come join us in adventure'. To the beat of their drum sir I did step forward ..... it was the 18th of May 1850 sir, they gave me a number ..... 3993 it be sir .... and a promise of a living as I signed my name where the sergeant pointed. Oh, how I recall my heart racing as I hurried back home to Cory to tell my father that his youngest son was a tailor no more but an honourable soldier in the Queen's favourites, the Scots Fusilier Guards.

My dear mother was afraid for me and afeared to lose her youngest son, but I do believe my father was proud of me and could see that I may find a better life this way.

.......... Are you still there sir? ....... I cannot see much any more .... it must be getting dark and the orderlies not yet lit the lamps.

I was at Alma sir, aye and at Inkerman too, such bloody fighting ….. the smell of gunpowder, blood and fear, …….twas fearsome desperate fighting sir, …. At Inkerman we were outnumbered, though we didn’t know it in the fog, …… fog so thick we didn’t know who was friend or foe till we saw their faces and bayonets …. Murderous times sir, … I can hear the screams now …

Twas September last we set siege to Sebastopol, four miserable winter months ago, a November storm sank our ships that carried the where with all to see us through, and now us have precious little to comfort. ........... did you know sir, they made me sergeant, and I be only a young man too. Not that you can see the stripes on my rags of uniform now ....... oh so different just one year ago when we marched past Buckingham palace and our gracious Queen Victoria, we marched tall and proud, oh how bright the colours in the late winter sun, the heavy rhythmic crump of black boots on gravel, flags a flying, officers a shouting, the band, the crowd … our Queen … we felt on top of the world sir … invincible we were. ....... oh, how so much has changed now sir, many a good friend has gone before me, George Ramsey, blacksmith, died just a few days ago ... same as I have got I reckons, ..... and good old Daniel Brown, another tailor like I he was sir, he was killed first day at Inkerman along with some hundred and seventy other good souls....... we lost the same at Alma sir...... tis a bloody business this war with the Russians but our worst enemy is nature herself by far. All we are sir, grocers, weavers, tailors, labourers and carpenters, brought to a foreign land as soldiers to die in disease hunger and cold.

Tis the men killed by Russian shot or bayonet that be the lucky ones. Theirs is pain no more, yet history will mark their sacrifice with honour sir, ..... what of us sir, who merely died a death we could have had at home sir, as many a good Cornishman has, …. are we not all comrades in arms sir, are we not all children of our country ….. are you still there sir, I fear I fall to a weary deep sleep …… I would my dear mother was near … please remember me sir, … I be Thomas Edwin Baker and so very far from home …. Du re bo genen ni oll ……..”

**

So spoke Thomas Baker one warm spring day as I brushed grass cuttings from his marker in the graveyard at Morwenstow.

Perhaps, should you stand and listen he'll 'speak' to you too.

For one, I’ll not forget him.

**

In the above story all the facts are as historians have recorded,

by poetic licence, his spoken words are mine; perhaps, if I were in his shoes, my words would be his too.

Ships lost on Morwenstow rocks for the relevant period.

Caledonia 1842

Phoenix 1843

Eliza 1846

Thomas Edwin Baker was baptised 29th October 1831

Enlisted in Scots Fusilier Guards on 18th May 1850 and died 16th January 1855

The old farm house at Cory burned to the ground in the late 1800s.

Richard Baker buried 13.3.1860 residing at Gooseham age 73.

Grace Baker buried 8.3.1863 residing at Cory

Reverend Robert Stephen Hawker was vicar at Morwenstow from 1834 for 41 years.

In 1854 the Scots Fusilier Guards sailed from Cork to start their journey to the Black Sea.

23rd February 1854 they paraded at Buckingham Palace in front of Queen Victoria.

They landed in the Crimea in September 1854 after first being deployed in Malta, Bulgaria and Turkey.

Thomas was entitled to the Crimea medal with clasps for Alma, Inkerman and Sebastopol. A medal he would never see.

14th November 1854 a great storm sank the British ships carrying winter provisions.

At Alma on 20th September 1854 the Scots Fusilier Guards lost 11 officers and 149 men; at Inkerman 5th November 1854 they lost 9 officers and 168 men (half their strength)

George and Daniel were indeed soldiers with Thomas.

Summer in the Crimea can be 30 degrees C. Winter can drop below freezing.

1849 cholera struck west Cornwall. 1849 – 1850 smallpox epidemic.

Where is Thomas buried? Some unknown grave in the East that is forever England; he likely died of disease; cholera was a big problem and can at times kill in only a few hours. If he had been transferred to the converted barracks at Scutari in Istanbul, Turkey it would have been recorded and it isn’t. Scutari was where Florence Nightingale did her pioneering work … which sadly was often ignored by the powers of the day. 6,000 died of cholera at Scutari.

‘Du re bo genen ni oll’ Cornish for ‘May God be with us all’

*********

Below is a poem about Thomas' life ,

written by my good friend, author and artist Sue Valentine.

**

Song of Thomas Baker

Sing me a song of life, sir, and I’ll sing you a song of the sea,

Of brave and noble men, sir, and who I came to be,

of how I strove to save us all, yet died just twenty three.

Pray listen to my tale sir, for I cannot tarry long

Embrace my words within your heart, and write my farewell song,

Sing it to those I leave behind, when I am finally gone.

Sing of a boy, a brother, a son, a proud and noble soul,

Sing of the men, who’d lost their lives under the seas that roll,

And sing of those that stayed at home, to count that awful toll.

Make it a song of wreckers, sir, of lowly deeds soon done,

Sing of those who laughed at toil, brother, father, son,

Tell of the Cornish coast we loved, under the ‘salty’ sun.

I trust I made my father smile, as I stood tall and proud,

My mother shed a tear for me, alone amongst the crowd

She feared the flag I fought for, would soon become my shroud.

I know I won’t go home now sir and I must say goodbye

To all of those who loved me, and all of those who cry,

Please ask them to remember me, please tell them where I lie.

I lived this life the best I could, I truly gave my all,

This light grows dim, if you’re still there, from grace I fear to fall,

‘Du re bo genen ni oll’, I hear my brother’s call. . .

written by my good friend, author and artist Sue Valentine.

**

Song of Thomas Baker

Sing me a song of life, sir, and I’ll sing you a song of the sea,

Of brave and noble men, sir, and who I came to be,

of how I strove to save us all, yet died just twenty three.

Pray listen to my tale sir, for I cannot tarry long

Embrace my words within your heart, and write my farewell song,

Sing it to those I leave behind, when I am finally gone.

Sing of a boy, a brother, a son, a proud and noble soul,

Sing of the men, who’d lost their lives under the seas that roll,

And sing of those that stayed at home, to count that awful toll.

Make it a song of wreckers, sir, of lowly deeds soon done,

Sing of those who laughed at toil, brother, father, son,

Tell of the Cornish coast we loved, under the ‘salty’ sun.

I trust I made my father smile, as I stood tall and proud,

My mother shed a tear for me, alone amongst the crowd

She feared the flag I fought for, would soon become my shroud.

I know I won’t go home now sir and I must say goodbye

To all of those who loved me, and all of those who cry,

Please ask them to remember me, please tell them where I lie.

I lived this life the best I could, I truly gave my all,

This light grows dim, if you’re still there, from grace I fear to fall,

‘Du re bo genen ni oll’, I hear my brother’s call. . .