'Red Watch' was written by former news reader and fire brigade enthusiast, Gordon Honeycombe in 1976. It had a lasting effect on my life. As part of a writing group we were asked to write something on a book of our choice . . . this one chose itself.

Red Watch Revisited.

Not reading any more, I closed the book, hardly able to control a stifled wail of sorrow and a well of tears. Tears I’d known some forty years before flooded back to me, filling my whole body with memories I thought I’d long left behind.

Red Watch was a book written by news reader and fire brigade enthusiast, Gordon Honeycombe in 1976, incidentally the drought year and one of our busiest. It begins with a reprint of a speech at a rotary club in London by the then chief officer of London, Joe Milner. Unusually, he takes sides with the men under his command . . . thinking that people should know what firemen sacrifice for a few pounds a week. He mentions two incidents, one where over fifty people were rescued by use of ladders and another of two firemen caught in a flashover, both so badly burned they must be suspended over their hospital beds, slowly and painfully over the next three days, they die. The newspaper headlines proclaim a national tragedy – not of these brave souls who risked and lost all, but of a dying Jeremy the Giraffe at London Zoo.

The book continues with the generality of life at a fire station, the routine of training, humour, attending incidents. . in fact I almost found that boring having my own memories that suited me better.

But then, then comes the fire at the hostel in Maida Vale, seven people are to die including a fireman trapped, lost and missing until they find his crushed body under collapsed masonry.

I remember reading this book, I may have slept that night or may not, I cannot remember, but I know as dawn broke I was still reading, unable to stop. I was as compelled to read on, as the London firemen were to find their missing comrade. I might as well have been there with them for all the intensity that filled my body and soul.

I was on duty that day . . . the book must be finished before I leave for work.

As dawn also broke for a young widow and an orphan and the news that the missing fireman was her own husband, I am not ashamed to say I cried into my cornflakes. Harry Pettit would have been much the same age as I, he would have joined in 1974, as did I, by December he was dead. In some ways I envy his heroic death, never sure if any one would miss me like they did Harry. The esteem in which he was held was never mine, though it is something that never happened I still miss what could have been.

I kept my copy of the book to share with others so that they might understand me and the work I chose to follow. It was and still remains a foolish notion, for thirty years on, I realise only those who served, could even begin to understand.

Red Watch Revisited.

Not reading any more, I closed the book, hardly able to control a stifled wail of sorrow and a well of tears. Tears I’d known some forty years before flooded back to me, filling my whole body with memories I thought I’d long left behind.

Red Watch was a book written by news reader and fire brigade enthusiast, Gordon Honeycombe in 1976, incidentally the drought year and one of our busiest. It begins with a reprint of a speech at a rotary club in London by the then chief officer of London, Joe Milner. Unusually, he takes sides with the men under his command . . . thinking that people should know what firemen sacrifice for a few pounds a week. He mentions two incidents, one where over fifty people were rescued by use of ladders and another of two firemen caught in a flashover, both so badly burned they must be suspended over their hospital beds, slowly and painfully over the next three days, they die. The newspaper headlines proclaim a national tragedy – not of these brave souls who risked and lost all, but of a dying Jeremy the Giraffe at London Zoo.

The book continues with the generality of life at a fire station, the routine of training, humour, attending incidents. . in fact I almost found that boring having my own memories that suited me better.

But then, then comes the fire at the hostel in Maida Vale, seven people are to die including a fireman trapped, lost and missing until they find his crushed body under collapsed masonry.

I remember reading this book, I may have slept that night or may not, I cannot remember, but I know as dawn broke I was still reading, unable to stop. I was as compelled to read on, as the London firemen were to find their missing comrade. I might as well have been there with them for all the intensity that filled my body and soul.

I was on duty that day . . . the book must be finished before I leave for work.

As dawn also broke for a young widow and an orphan and the news that the missing fireman was her own husband, I am not ashamed to say I cried into my cornflakes. Harry Pettit would have been much the same age as I, he would have joined in 1974, as did I, by December he was dead. In some ways I envy his heroic death, never sure if any one would miss me like they did Harry. The esteem in which he was held was never mine, though it is something that never happened I still miss what could have been.

I kept my copy of the book to share with others so that they might understand me and the work I chose to follow. It was and still remains a foolish notion, for thirty years on, I realise only those who served, could even begin to understand.

When danger came . . .

Not for them to say, ’We’re brave’, though risk their lives they would,

when danger came with threat of death, through hope and hell, they stood.

To a man, the foe they’d fight, regardless of its form,

and danger comes with threat of death, in darkness, fire and storm.

I know their thoughts; I feel their pain, for with them I once stood,

and danger came with threat of death, but never cry they would.

When fearful shouts for help came in, loud bells would raise alarm,

then danger and its threat of death was met with strength and calm.

The siren wailed, the road had cleared and urgently they'd drive.

While danger stalks with threat of death. ‘Hang on, 'till they arrive.’

That dreadful fire, it seemed to breathe, and life to terror give,

as danger grew with threat of death, they must not let it live.

Fire is out and people saved, the crew returned to base,

all danger quelled from threat of death, relief on every face.

No coin they ask, but honour due; reporters, beg their name,

though danger lurks with threat of death, none who’s there, seek fame.

C RJS 2016

Stories in order of appearance:-

Tales from the Smoke House – a BAI’s story.

Life jackets? . . . and we called it training !

Cambridge Fire Station, a story and pictures.

Truth, Fire, Duty, Compassion, Honour, Comrades. (A true story.

Northamptonshire County Fire Service 1974.)

Tales from the Smoke House – a BAI’s story.

Life jackets? . . . and we called it training !

Cambridge Fire Station, a story and pictures.

Truth, Fire, Duty, Compassion, Honour, Comrades. (A true story.

Northamptonshire County Fire Service 1974.)

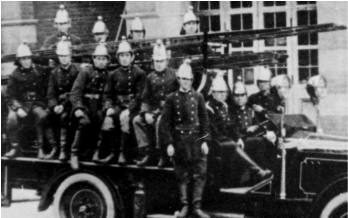

We who live today can never know the lives they lived back then.

All is changed.

Some things we've gained but

much is lost.

Beware, you lose some more !

Railway carriage - what was left of it after a Fire Service training exercise went slightly out of hand. An officer thing, you know.

Railway carriage - what was left of it after a Fire Service training exercise went slightly out of hand. An officer thing, you know.

Tales from the Smoke House – a BAI’s story.

You'll find the truth of it all in here! The truth they'll rarely tell.

Often it's a truth you do not want to know.

From basic training with pumps and ladders, the fireman would move on to more advanced training in the use of Breathing Apparatus (BA); he would learn and practice search and rescue techniques, care and maintenance of equipment, procedures about entry control, fire-fighting, emergencies and teamwork. It’s not just teamwork, but individual skill, knowledge and intuition, that makes a good BA wearer, for once the team is inside the incident they are on their own; often blinded by smoke and darkness as they peer through their misted up visor. Cut off by toxic smoke and dangerous conditions from the rest of the crew and officers – whatever the BA team face inside the building they face it alone, in the dark in more ways than one, in a strange place.

The Fireman must know how to find his way back to safety, but be able to conduct ‘entrapped procedures’ should his route be barred by fire or collapse. Horror stories of fire-fighter’s deaths in the most panic stricken and desperate of ends should be enough to focus the BA wearer’s mind on his means of escape. When air runs out in the cylinder, desperate men have torn off their masks, breaking the neoprene straps, only to succumb to the choking hot gases that envelop them; finger nails torn from clawing hands as they tried to escape rooms that were not their way out –though they thought they were. Orders given to flood underground bunkers to extinguish a fire, knowing that the BA men sent in earlier must be dead already, their air run out long before – surely enough to focus the BA wearer’s mind.

The BA wearer must know all the secrets of doors and their mechanisms, what height the handles – and how many too. Sliding doors and recessed handles, doors that swing closed behind them with no handles on the inside, and doors that open from upper floors straight to the long drop to the street below. A never ending catalogue of pitfalls and traps must be learned – glass doors, mirrors, electricity, moving machinery, gas cylinders, gas leaks, fat fryers and on and on ……. As the BA wearer progresses in experience he nurtures his will to teach others of his learning.

In the old days the heavy compressed air cylinder was made of thick steel, the face mask had an inner mask that pinched the wearer’s nose uncomfortably throughout the wear ….. No chance to scratch an itch …. And woe betide the wearer that inadvertently sneezed. A length of strong personal line was attached to the set harness, his pressure gauge allowed him to assess ‘time’ past and ‘time’ left, also attached at chest height was the distress signal unit –The wearer pressed a button and a high pitched buzzer sounded, (useless in high expansion foam) The early ones sometimes only worked if you gave them a good whack – it didn’t stop their use. The torch was a low output affair as used down coal mines – it’s hard to know how miners could see anything with them either !! – usually made of copper and on a simple hook this lamp would hang on the chest strap of the BA set …….. that is until it slipped off – a frequent occurrence.

The Breathing Apparatus Instructor (BAI) had to know all this and more, he also had to know how to set up and monitor exercises efficiently and safely, how to instruct and guide the student BA wearer and mentor the more experienced wearers and those Officers who came once a year for their refresher training.

Ah! The Officer’s refreshers – those Officers who professed to know so much, so important, who changed people’s lives with Masonic promotion opportunities, earned lots more than us and did much less. The BA refresher – a chance to see that they did some real work – on occasions it wasn’t unknown for extra fuel to go on a hotter fire to settle old scores!!

It is, I suppose, to be expected that they would make mistakes but consider this, that at real fires they would be responsible for the direction and safety of BA crews at the incident. So, was it really important if they put their BA sets on upside down, tied themselves up in their own lines, or separated from the rest of the crew? …. You make your choice!

For the operational BA wearer all these could prove fatal errors – and these Officers were their leaders.

It was up to the BAI to put all this right.

In ‘tales from the smoke house’, the smoke house is a term given to a room or building in which heat and smoke are produced either artificially or with real fires.

All new retained fire-fighters always attended a BA initial course with qualified training staff consisting of a Station Officer and two or three Junior Officers. Someone amongst the staff had to be a BAI, if not all of them. I recall one such course when our Station Officer was not a BAI, but being the senior rank he was in charge, and what he said, went. It was going to be a week like no other; if my memory serves me well we only had three of our own retained fire-fighters to train but two firemen from the nearby USAF military base were to join us.

It was evident from day one that our Station Officer was going to show these ‘colonials’ just what ‘real’ firemen were made of. On day one, under ‘easy’ conditions, just to acclimatise wearers to sets and procedures, I had one wearer try to pull his mask off. I did all I could, without physically restraining him, to stop him and calm the panic; to remove the mask other than outside with the Entry Control Officer is a cardinal sin, especially in panic – what if he did this on a real working job – how many of us would die trying to save him – never mind his own life.

Well, it was to no avail, he tore off his face mask, then realised the enormity of his actions. As he calmed down his sorrow was evident. The matter was discussed with the Station Officer and it was decided that, as we were short on numbers and the Fireman realised the error of his ways, that he could stay on the course ……… until two days later that is!

He resigned and left on Wednesday lunchtime, at the same time as one of the USAF firemen, who’d been sick in his facemask while in strenuous heat and smoke conditions at one of our smoke houses – again a serious matter and potentially fatal. The exhalation valve is designed for the passage of air, not stomach contents, and the small ori-nasal inner mask is also where your fresh air comes in – so you end up breathing in your own vomit – yup – not nice and when you are in a toxic atmosphere to remove your mask is no better an option!

So, we are now down by two, and by the end of the afternoon we were three down with the remaining USAF fireman succumbing to the rigours of the underground tunnel crawl – a gruelling simulated sewer exercise rescuing a full size, 12 stone, dummy – (only one team in all the exercises I took part in ever succeeded in making the whole distance, usually they would only make half way.)

Now we only had two students – but this was still ok, as they worked in a pair while one of us did the Entry Control job outside. Next day, Thursday it was, our leader had gone ahead to set up the smoke house at a village station. Inside there were many obstacles - an old factory roller conveyer, furniture partitions, a set of stairs, and crawl areas as well as a small fire. The crawl areas were 45 gallon drums with the ends cut off so that the BA set on the Fireman’s back ensured that he would have to lie prone in order to squeeze through. As you went through, reaching forward with your arms, it wasn’t unusual for the sleeves of your fire tunic to ride up, exposing your arm – now, coupled with the fact that the Station Officer had placed one of the big fan driven industrial paraffin heaters butting up to one of these drums so it was glowing red hot, it wasn’t surprising that one of our chaps got burnt. Now we’re down to one!

I drove our injured chap to the hospital for treatment – he was ok and well enough to attend the last day. As BAI’s I don’t think we would have lost any students, as our point to prove was not to impress but to teach …. But we were not in charge.

I was a BAI working at the training centre attached to a small central fire station, which, in the early days had a small brick shed like fire house. It had a small but tortuous two level labyrinth of wooden ‘tunnels’ with some very constricted and awkward turns – if some one was ever trapped in there for real it would have been extremely difficult to get them out due to the restricted access. Our best hope for an emergency procedure was to open the two external doors and extinguish the fire, so getting fresh air into the victim.

We would take it in turns to be the BAI safety observer, (on the inside!), or the safety officer outside that kept an eye on things externally, watching the entry time clock, the temperature and listening for distress signals.

I recall once laying on the hot wooden boards of the upper level; the heat from the boards alone was paining my legs, as I lay there in that braising carcinogenic concoction of hot gases, I knew it would be impossible for me to go any higher and over the partition wall to drop down to the ground floor near the fire. It can be only 50 degrees C near the floor but as much as 500 degrees C at the ceiling – I’m sure you can work out the consequences yourself as we roast meat in the oven at only 200 degrees!

So, there I am laying there, the observer and ‘rescue’ man, waiting for the door to open and the BA crews to enter for their training. The door did open – but it was Dave, an old fashioned BAI, – only opening the door so he could throw some more fuel on the fire! So, you see, the BAI was in the thick of it much longer than the crews, we were first in and always last out.

During one of the exercises in that little fire house we nearly ‘lost’ an officer, and a senior one at that. It was a guide line exercise, the crew of two would carry a big bag of special ‘string’, one end of which was tied securely to the outside of the building in fresh air; they could always then retrace their steps to safety. Come to think of it, it was a very silly place to do such an exercise – it was more suited to big spaces – still we just followed orders.

The Officers were nearly out; they were just negotiating one of the tightest corners in the lower ‘tomb’ level when the lead officer became entangled in the guide line, unable to free himself due to the restricted space, nor his colleague could help for the same reason. The small smoke filled fire house is little more than a gas chamber; their only hope is the cool air they breathe from the cylinders on their backs.

A distress signal sounded; the Station Officer in charge, shouting, “Get the doors open!” By doing so we could get fresh air and light inside. From where the Station Officer crouched in the open doorway, hot smoke billowing out above his head, he could see the trapped man, who was trying to pull his face mask off. Our Station Officer screamed at him, “keep your mask on; keep your mask on!”

All to no avail; the mask was off, but luckily by then cool fresh air was filling the lower ground of the fire house.

The reason for his panic?

He had no air left! At the training centre we were experiencing problems with this particular type of breathing apparatus. (Ego and a sense of justice permit me to tell you it was me that discovered and reported the fault – though we continued to use those sets for some time before the problem was resolved. Of course those with power and high office weren’t those who ever had to wear these sets – perhaps then it would have been fixed earlier … or is that too cynical?).

When the wearer breathes, reduced pressure in the mask triggers a flow of air until the pressure rises again and turns it off … until the next breath. The process is quite noisy and in order to listen to others it was necessary to hold your breath. The fault in our sets was that occasionally at very low pressures when you were at your most vulnerable, tired and short of air, the air supply would trip into a constant flow, wasting your air and gushing it out of the exhalation valve, your ten minute safety margin reduced to two or less – and nothing you could do about it – please spare a moment to consider this.

Probably the fact that we nearly killed one of our senior officers focussed the mind of those responsible for our safety, and who previously had deaf ears to the fault!!

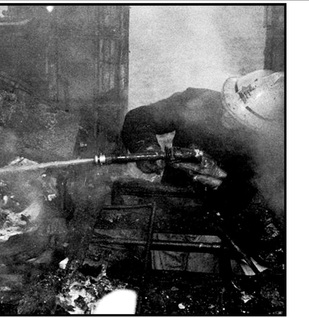

Before I was a BAI, and before the health and safety executive had too strong a strangle hold on the fire brigade, we could light fires and use them for realistic practical training. I was involved in one such exercise that spelled the death knell for live fires at our main station’s smoke house.

It was a building of two floors with an internal concrete stairway against the back wall; there were large semi permanent vertical partitions within the building to make life more complicated and challenging and a huge heavy fire basket sat in the middle of the ground floor.

The Watch (a group of Fire-fighters that always worked together on shift) was split into two, one half to wear BA and do the training and the other half to do all the organising outside. Then, at a later date we were to change roles, ….. we never were to have our ‘revenge’.

Our task was to collect 20 kilo drums from the upper level of the windowless blacked out building, and deposit them on the ground floor. We were all in pairs and connected by our short personal lines (4 feet) to our partner.

Well, it was going OK, we made a couple of trips up the stairs and back down with our loads. It was becoming rather hot in there though, as flames from the fire rose to the ceiling and hurried across to the stairs where they met us on our way down. I called a halt to any more crews going back up. The fire was accelerating in intensity – thanks to a big chap called Andy who kept throwing sheets of hardboard on!

From our position we could see the flames now crossing the ceiling and entering the stairway about halfway up. We still had one pair of wearers upstairs; then they appeared; the lead man taking the steps in haste and two at a time – not bad in boots, fire kit and BA, dragged behind him, staggering like a puppet, on the end of the personal line, his colleague – a lighter and less fit man than he, it must be said – how he made his feet land on steps we’ll never know.

We were all down and relatively safe and we exited through the emergency doors into the fresh cool air and reported to the watching Officer – but he had already seen the state of the fire through the open door and ordered the exercise aborted and the fire extinguished.

The last man down? Much to the amusement of all the Watch, his hair was singed all down one side, changing the shape of some sort of curly wig type ‘perm’ he’d had done the day before – that too had amused us.

We couldn’t wait for the ‘return match’, and then ‘we’d show ‘em what a real fire was all about’ – it was never to be, live fires were discontinued at our station from that day. ….. Damn!

What happens next is a real ‘must’ …… for the training centre was to have a new, state of the art, thoroughly researched and innovative architect designed operational training building, which was to be constructed in place of the small brick, labyrinth gas chamber we mentioned earlier.

During its construction, someone, and still anonymous, but probably off of the operational fire station and not training centre, had been nosing about in the building at night. They were fairly certain someone had been in there when they found the hardened footprints in their concrete the next day!

This brought about a massive ‘overkill’ response – one that any sane person would look back on with regret – ‘Anyone caught entering the smoke house will be put on a disciplinary charge’.

Fair enough I suppose, they were in charge, but how useful it would have been for all concerned if those who were actually going to use the building could be aware of what was going on – and dare I say it, contribute? It might have stopped them building a multi pitch roofs, (excellent and just what we did want), which were clad with highly brittle concrete roof tiles which cracked or broke when we put any weight on them, (not at all what we wanted). We could no longer use the roof for any training, if we did, the roof would soon be bald.

After the building was opened with due pomp and ceremony and the Chief Fire Officer posing for the press, we began to use it; things soon started to go wrong. The fire room, (lined with special ceramic tiles – that just happened to be carcinogenic – still, not to worry, that went for most of the dust and fire bi-products that layered the inside of the building) had a big insulated heavy metal door to the outside and two similar doors on the inside, above which were transom ‘doors/openings’, which slid on rollers so that we could open or close the amount of heat, fire and good old sparks entering the training area. Well, these didn’t last five minutes; they failed on their first use, also to evacuate the smoke in an emergency, great fans were fitted in the drill tower and a great, two floor height louvered metal shutters fitted to allow the fresh air in. This they did rather efficiently – ‘good thing’, I hear you say, except that they too failed – in the open position, negating the value of a once dark and hot smoky smoke house.

You might think that we, the real and only users of the building might become a little frustrated by then – and you would be right.

Still, all was not lost, someone had a brilliant idea – (and was probably promoted instantly for it!!) – why not get the users and the designers together, let them sit round the table and sort it out!

I was present at the meeting. The architects had designed a fire room in which we could light large fires to heat the building; they were quite shocked when we told them that the temperature at the head of stairs was as high as 160 degrees C and the fire room was achieving temperatures of about 400 degrees Centigrade. “Oh dear”, they said, “We didn’t know it would get that hot …… the solenoids we used are only good for about 80 degrees.” Well, that explains why they didn’t last too long eh?

“What about fitting better solenoids?” we offered.

“Not possible,” they replied, “they don’t make any that cope with that heat”

So now we have a complex design built around solenoids you can’t buy; do you think early consultation might have averted this? So do I.

So, here we have a state of the art, architect designed operational training building that is no longer operational. We had things sorted in the end, resorting to simple manually rigged and operated sytems that did the job – sort of.

If only they had let the BAIs in at the beginning.

The new building had a control room with a great electronic ‘dashboard’, most of which we never used. There was a monitor through which infra red camera images could be relayed and recorded – very rarely done as the connectors for the camera inside the building didn’t like the dust, heat, smoke and humidity either. We could play sound effects throughout various areas of the building of our choice – trouble is they didn’t supply us with any. The tape we used was a multiple recording of a small extract from a forensic fire reconstruction video; it had a realistic fire and suitable noises to accompany. During the filming of the test the scientists were caught out by the speed and ferocity of a quickly developing and intense fire, they had to evacuate the area in a hurry with someone bellowing, “everybody out! Everybody out!” This shout was also on the recording we were using. I remember once we had just sent a crew in rigged in BA to affect a search and rescue operation in heat and smoke, we were playing the tape to create a more realistic scenario, but it was not long before the crews burst out the emergency exits.

“What the devil are you doing out here, where’s the casualty?” a BAI demanded.

“We heard a voice saying everybody out!” their muffled voices shouting through their masks.

The BAI, in his most pleasant and diplomatic manner, in a soft and friendly voice (if you can believe that !) explained,

“Yes you did! …. But that’s NOT for YOU; you’re the fire brigade - back in and be smart about it!”

***

There were manholes in the floors, with 4 foot drops shielded by heavy metal covers which we could remove for different exercises, like basements or sewers etc. Even though instructors were totally familiar with the layout of the building, (perhaps there’s a clue there), at least two fell down them; I know of at least five that suffered the same fate. Instructors, BAIs, also on occasions faced more immediate life threatening experiences.

The fire room had a big metal brazier, the thick metal bars of which were sagging and distorted from the intense heat generated in there. There were no visible door handles on the inside, the only light, the light from the fire. The fire would be stacked with paper, kindling and heavy wooden pallets, and then lit by the BAI some thirty minutes before the visiting fire crews arrived for BA training. With the fire burning well, it would be topped up with more pallets, each being carried through the doorway and thrown in sending a shower of sparks into the air, the BAI shielding his face as best he could from the radiating heat; the heavy metal and insulated self closing door propped open against closure.

That heavy metal door was to almost take the lives of two BAIs on separate occasions. The events were officially kept secret by the first victim, though privately shared between us fellow BAIs; I’ll share just one with you.

It was a winter dark evening time and the BAI was there early and alone. He entered the fire room and lit the fire; breathing apparatus was never used in these circumstances for practical and procedural reasons.

The flame started to rise and take hold; the fire had a firm grip on the timbers by the time our BAI – a big man – heard the unmistakable loud metallic thud and clang of that great metal door slamming shut and, outside, the locking mechanism snapping into place. For him it was too late to dismantle the fire of fuel, serious burns would be inevitable, he rushed to the door and searched for a handle – if there ever was one under the insulation and thick wire mesh that held it in place we never found it – anyway it’s an irrelevance – he was not going to find it that night! He needed to get out of that fire room, and damn quickly, no good waiting for the arrival of the fire crews, they wouldn’t think of looking in there, literally the last place they would look, by then he would be long dead; having died the most terrifying and slow death by the radiated heat; in the morning it might be that just a few bones and buttons would tell the tale.

Well, fear and an overwhelming desire to get the hell out was coursing through his very being.

There was a way out!

It was through the same hole that those soon to be searing hot flames would be leaving and then it would be impossible – one breath of those hot gases and the lungs would be irretrievably and fatally damaged. He had to act quickly; how he managed to pull himself up to the height of those transom openings above the inner doors even he will not know, how he managed to squeeze his huge frame through that small opening he will never know, and how he managed in the darkness to find the floor some eight feet down and head first he will not know. What he does know is that he is out – alive – safe.

What he achieved would surely be impossible if it were not for those terrifying circumstances in which he had found himself.

Some of what we did, what we saw, taught, discovered and learned is always with us in our minds. We had to know more, experience more and stay longer than those we strived to help improve their chances of survival when wearing BA out there in the world of real fires, that didn’t have sprinklers and controlled ventilation systems when life was threatened.

I hope I’ve given you a taste of some of the honest and sometimes truly frightening tales from the smoke house. This is a true story.

You'll find the truth of it all in here! The truth they'll rarely tell.

Often it's a truth you do not want to know.

From basic training with pumps and ladders, the fireman would move on to more advanced training in the use of Breathing Apparatus (BA); he would learn and practice search and rescue techniques, care and maintenance of equipment, procedures about entry control, fire-fighting, emergencies and teamwork. It’s not just teamwork, but individual skill, knowledge and intuition, that makes a good BA wearer, for once the team is inside the incident they are on their own; often blinded by smoke and darkness as they peer through their misted up visor. Cut off by toxic smoke and dangerous conditions from the rest of the crew and officers – whatever the BA team face inside the building they face it alone, in the dark in more ways than one, in a strange place.

The Fireman must know how to find his way back to safety, but be able to conduct ‘entrapped procedures’ should his route be barred by fire or collapse. Horror stories of fire-fighter’s deaths in the most panic stricken and desperate of ends should be enough to focus the BA wearer’s mind on his means of escape. When air runs out in the cylinder, desperate men have torn off their masks, breaking the neoprene straps, only to succumb to the choking hot gases that envelop them; finger nails torn from clawing hands as they tried to escape rooms that were not their way out –though they thought they were. Orders given to flood underground bunkers to extinguish a fire, knowing that the BA men sent in earlier must be dead already, their air run out long before – surely enough to focus the BA wearer’s mind.

The BA wearer must know all the secrets of doors and their mechanisms, what height the handles – and how many too. Sliding doors and recessed handles, doors that swing closed behind them with no handles on the inside, and doors that open from upper floors straight to the long drop to the street below. A never ending catalogue of pitfalls and traps must be learned – glass doors, mirrors, electricity, moving machinery, gas cylinders, gas leaks, fat fryers and on and on ……. As the BA wearer progresses in experience he nurtures his will to teach others of his learning.

In the old days the heavy compressed air cylinder was made of thick steel, the face mask had an inner mask that pinched the wearer’s nose uncomfortably throughout the wear ….. No chance to scratch an itch …. And woe betide the wearer that inadvertently sneezed. A length of strong personal line was attached to the set harness, his pressure gauge allowed him to assess ‘time’ past and ‘time’ left, also attached at chest height was the distress signal unit –The wearer pressed a button and a high pitched buzzer sounded, (useless in high expansion foam) The early ones sometimes only worked if you gave them a good whack – it didn’t stop their use. The torch was a low output affair as used down coal mines – it’s hard to know how miners could see anything with them either !! – usually made of copper and on a simple hook this lamp would hang on the chest strap of the BA set …….. that is until it slipped off – a frequent occurrence.

The Breathing Apparatus Instructor (BAI) had to know all this and more, he also had to know how to set up and monitor exercises efficiently and safely, how to instruct and guide the student BA wearer and mentor the more experienced wearers and those Officers who came once a year for their refresher training.

Ah! The Officer’s refreshers – those Officers who professed to know so much, so important, who changed people’s lives with Masonic promotion opportunities, earned lots more than us and did much less. The BA refresher – a chance to see that they did some real work – on occasions it wasn’t unknown for extra fuel to go on a hotter fire to settle old scores!!

It is, I suppose, to be expected that they would make mistakes but consider this, that at real fires they would be responsible for the direction and safety of BA crews at the incident. So, was it really important if they put their BA sets on upside down, tied themselves up in their own lines, or separated from the rest of the crew? …. You make your choice!

For the operational BA wearer all these could prove fatal errors – and these Officers were their leaders.

It was up to the BAI to put all this right.

In ‘tales from the smoke house’, the smoke house is a term given to a room or building in which heat and smoke are produced either artificially or with real fires.

All new retained fire-fighters always attended a BA initial course with qualified training staff consisting of a Station Officer and two or three Junior Officers. Someone amongst the staff had to be a BAI, if not all of them. I recall one such course when our Station Officer was not a BAI, but being the senior rank he was in charge, and what he said, went. It was going to be a week like no other; if my memory serves me well we only had three of our own retained fire-fighters to train but two firemen from the nearby USAF military base were to join us.

It was evident from day one that our Station Officer was going to show these ‘colonials’ just what ‘real’ firemen were made of. On day one, under ‘easy’ conditions, just to acclimatise wearers to sets and procedures, I had one wearer try to pull his mask off. I did all I could, without physically restraining him, to stop him and calm the panic; to remove the mask other than outside with the Entry Control Officer is a cardinal sin, especially in panic – what if he did this on a real working job – how many of us would die trying to save him – never mind his own life.

Well, it was to no avail, he tore off his face mask, then realised the enormity of his actions. As he calmed down his sorrow was evident. The matter was discussed with the Station Officer and it was decided that, as we were short on numbers and the Fireman realised the error of his ways, that he could stay on the course ……… until two days later that is!

He resigned and left on Wednesday lunchtime, at the same time as one of the USAF firemen, who’d been sick in his facemask while in strenuous heat and smoke conditions at one of our smoke houses – again a serious matter and potentially fatal. The exhalation valve is designed for the passage of air, not stomach contents, and the small ori-nasal inner mask is also where your fresh air comes in – so you end up breathing in your own vomit – yup – not nice and when you are in a toxic atmosphere to remove your mask is no better an option!

So, we are now down by two, and by the end of the afternoon we were three down with the remaining USAF fireman succumbing to the rigours of the underground tunnel crawl – a gruelling simulated sewer exercise rescuing a full size, 12 stone, dummy – (only one team in all the exercises I took part in ever succeeded in making the whole distance, usually they would only make half way.)

Now we only had two students – but this was still ok, as they worked in a pair while one of us did the Entry Control job outside. Next day, Thursday it was, our leader had gone ahead to set up the smoke house at a village station. Inside there were many obstacles - an old factory roller conveyer, furniture partitions, a set of stairs, and crawl areas as well as a small fire. The crawl areas were 45 gallon drums with the ends cut off so that the BA set on the Fireman’s back ensured that he would have to lie prone in order to squeeze through. As you went through, reaching forward with your arms, it wasn’t unusual for the sleeves of your fire tunic to ride up, exposing your arm – now, coupled with the fact that the Station Officer had placed one of the big fan driven industrial paraffin heaters butting up to one of these drums so it was glowing red hot, it wasn’t surprising that one of our chaps got burnt. Now we’re down to one!

I drove our injured chap to the hospital for treatment – he was ok and well enough to attend the last day. As BAI’s I don’t think we would have lost any students, as our point to prove was not to impress but to teach …. But we were not in charge.

I was a BAI working at the training centre attached to a small central fire station, which, in the early days had a small brick shed like fire house. It had a small but tortuous two level labyrinth of wooden ‘tunnels’ with some very constricted and awkward turns – if some one was ever trapped in there for real it would have been extremely difficult to get them out due to the restricted access. Our best hope for an emergency procedure was to open the two external doors and extinguish the fire, so getting fresh air into the victim.

We would take it in turns to be the BAI safety observer, (on the inside!), or the safety officer outside that kept an eye on things externally, watching the entry time clock, the temperature and listening for distress signals.

I recall once laying on the hot wooden boards of the upper level; the heat from the boards alone was paining my legs, as I lay there in that braising carcinogenic concoction of hot gases, I knew it would be impossible for me to go any higher and over the partition wall to drop down to the ground floor near the fire. It can be only 50 degrees C near the floor but as much as 500 degrees C at the ceiling – I’m sure you can work out the consequences yourself as we roast meat in the oven at only 200 degrees!

So, there I am laying there, the observer and ‘rescue’ man, waiting for the door to open and the BA crews to enter for their training. The door did open – but it was Dave, an old fashioned BAI, – only opening the door so he could throw some more fuel on the fire! So, you see, the BAI was in the thick of it much longer than the crews, we were first in and always last out.

During one of the exercises in that little fire house we nearly ‘lost’ an officer, and a senior one at that. It was a guide line exercise, the crew of two would carry a big bag of special ‘string’, one end of which was tied securely to the outside of the building in fresh air; they could always then retrace their steps to safety. Come to think of it, it was a very silly place to do such an exercise – it was more suited to big spaces – still we just followed orders.

The Officers were nearly out; they were just negotiating one of the tightest corners in the lower ‘tomb’ level when the lead officer became entangled in the guide line, unable to free himself due to the restricted space, nor his colleague could help for the same reason. The small smoke filled fire house is little more than a gas chamber; their only hope is the cool air they breathe from the cylinders on their backs.

A distress signal sounded; the Station Officer in charge, shouting, “Get the doors open!” By doing so we could get fresh air and light inside. From where the Station Officer crouched in the open doorway, hot smoke billowing out above his head, he could see the trapped man, who was trying to pull his face mask off. Our Station Officer screamed at him, “keep your mask on; keep your mask on!”

All to no avail; the mask was off, but luckily by then cool fresh air was filling the lower ground of the fire house.

The reason for his panic?

He had no air left! At the training centre we were experiencing problems with this particular type of breathing apparatus. (Ego and a sense of justice permit me to tell you it was me that discovered and reported the fault – though we continued to use those sets for some time before the problem was resolved. Of course those with power and high office weren’t those who ever had to wear these sets – perhaps then it would have been fixed earlier … or is that too cynical?).

When the wearer breathes, reduced pressure in the mask triggers a flow of air until the pressure rises again and turns it off … until the next breath. The process is quite noisy and in order to listen to others it was necessary to hold your breath. The fault in our sets was that occasionally at very low pressures when you were at your most vulnerable, tired and short of air, the air supply would trip into a constant flow, wasting your air and gushing it out of the exhalation valve, your ten minute safety margin reduced to two or less – and nothing you could do about it – please spare a moment to consider this.

Probably the fact that we nearly killed one of our senior officers focussed the mind of those responsible for our safety, and who previously had deaf ears to the fault!!

Before I was a BAI, and before the health and safety executive had too strong a strangle hold on the fire brigade, we could light fires and use them for realistic practical training. I was involved in one such exercise that spelled the death knell for live fires at our main station’s smoke house.

It was a building of two floors with an internal concrete stairway against the back wall; there were large semi permanent vertical partitions within the building to make life more complicated and challenging and a huge heavy fire basket sat in the middle of the ground floor.

The Watch (a group of Fire-fighters that always worked together on shift) was split into two, one half to wear BA and do the training and the other half to do all the organising outside. Then, at a later date we were to change roles, ….. we never were to have our ‘revenge’.

Our task was to collect 20 kilo drums from the upper level of the windowless blacked out building, and deposit them on the ground floor. We were all in pairs and connected by our short personal lines (4 feet) to our partner.

Well, it was going OK, we made a couple of trips up the stairs and back down with our loads. It was becoming rather hot in there though, as flames from the fire rose to the ceiling and hurried across to the stairs where they met us on our way down. I called a halt to any more crews going back up. The fire was accelerating in intensity – thanks to a big chap called Andy who kept throwing sheets of hardboard on!

From our position we could see the flames now crossing the ceiling and entering the stairway about halfway up. We still had one pair of wearers upstairs; then they appeared; the lead man taking the steps in haste and two at a time – not bad in boots, fire kit and BA, dragged behind him, staggering like a puppet, on the end of the personal line, his colleague – a lighter and less fit man than he, it must be said – how he made his feet land on steps we’ll never know.

We were all down and relatively safe and we exited through the emergency doors into the fresh cool air and reported to the watching Officer – but he had already seen the state of the fire through the open door and ordered the exercise aborted and the fire extinguished.

The last man down? Much to the amusement of all the Watch, his hair was singed all down one side, changing the shape of some sort of curly wig type ‘perm’ he’d had done the day before – that too had amused us.

We couldn’t wait for the ‘return match’, and then ‘we’d show ‘em what a real fire was all about’ – it was never to be, live fires were discontinued at our station from that day. ….. Damn!

What happens next is a real ‘must’ …… for the training centre was to have a new, state of the art, thoroughly researched and innovative architect designed operational training building, which was to be constructed in place of the small brick, labyrinth gas chamber we mentioned earlier.

During its construction, someone, and still anonymous, but probably off of the operational fire station and not training centre, had been nosing about in the building at night. They were fairly certain someone had been in there when they found the hardened footprints in their concrete the next day!

This brought about a massive ‘overkill’ response – one that any sane person would look back on with regret – ‘Anyone caught entering the smoke house will be put on a disciplinary charge’.

Fair enough I suppose, they were in charge, but how useful it would have been for all concerned if those who were actually going to use the building could be aware of what was going on – and dare I say it, contribute? It might have stopped them building a multi pitch roofs, (excellent and just what we did want), which were clad with highly brittle concrete roof tiles which cracked or broke when we put any weight on them, (not at all what we wanted). We could no longer use the roof for any training, if we did, the roof would soon be bald.

After the building was opened with due pomp and ceremony and the Chief Fire Officer posing for the press, we began to use it; things soon started to go wrong. The fire room, (lined with special ceramic tiles – that just happened to be carcinogenic – still, not to worry, that went for most of the dust and fire bi-products that layered the inside of the building) had a big insulated heavy metal door to the outside and two similar doors on the inside, above which were transom ‘doors/openings’, which slid on rollers so that we could open or close the amount of heat, fire and good old sparks entering the training area. Well, these didn’t last five minutes; they failed on their first use, also to evacuate the smoke in an emergency, great fans were fitted in the drill tower and a great, two floor height louvered metal shutters fitted to allow the fresh air in. This they did rather efficiently – ‘good thing’, I hear you say, except that they too failed – in the open position, negating the value of a once dark and hot smoky smoke house.

You might think that we, the real and only users of the building might become a little frustrated by then – and you would be right.

Still, all was not lost, someone had a brilliant idea – (and was probably promoted instantly for it!!) – why not get the users and the designers together, let them sit round the table and sort it out!

I was present at the meeting. The architects had designed a fire room in which we could light large fires to heat the building; they were quite shocked when we told them that the temperature at the head of stairs was as high as 160 degrees C and the fire room was achieving temperatures of about 400 degrees Centigrade. “Oh dear”, they said, “We didn’t know it would get that hot …… the solenoids we used are only good for about 80 degrees.” Well, that explains why they didn’t last too long eh?

“What about fitting better solenoids?” we offered.

“Not possible,” they replied, “they don’t make any that cope with that heat”

So now we have a complex design built around solenoids you can’t buy; do you think early consultation might have averted this? So do I.

So, here we have a state of the art, architect designed operational training building that is no longer operational. We had things sorted in the end, resorting to simple manually rigged and operated sytems that did the job – sort of.

If only they had let the BAIs in at the beginning.

The new building had a control room with a great electronic ‘dashboard’, most of which we never used. There was a monitor through which infra red camera images could be relayed and recorded – very rarely done as the connectors for the camera inside the building didn’t like the dust, heat, smoke and humidity either. We could play sound effects throughout various areas of the building of our choice – trouble is they didn’t supply us with any. The tape we used was a multiple recording of a small extract from a forensic fire reconstruction video; it had a realistic fire and suitable noises to accompany. During the filming of the test the scientists were caught out by the speed and ferocity of a quickly developing and intense fire, they had to evacuate the area in a hurry with someone bellowing, “everybody out! Everybody out!” This shout was also on the recording we were using. I remember once we had just sent a crew in rigged in BA to affect a search and rescue operation in heat and smoke, we were playing the tape to create a more realistic scenario, but it was not long before the crews burst out the emergency exits.

“What the devil are you doing out here, where’s the casualty?” a BAI demanded.

“We heard a voice saying everybody out!” their muffled voices shouting through their masks.

The BAI, in his most pleasant and diplomatic manner, in a soft and friendly voice (if you can believe that !) explained,

“Yes you did! …. But that’s NOT for YOU; you’re the fire brigade - back in and be smart about it!”

***

There were manholes in the floors, with 4 foot drops shielded by heavy metal covers which we could remove for different exercises, like basements or sewers etc. Even though instructors were totally familiar with the layout of the building, (perhaps there’s a clue there), at least two fell down them; I know of at least five that suffered the same fate. Instructors, BAIs, also on occasions faced more immediate life threatening experiences.

The fire room had a big metal brazier, the thick metal bars of which were sagging and distorted from the intense heat generated in there. There were no visible door handles on the inside, the only light, the light from the fire. The fire would be stacked with paper, kindling and heavy wooden pallets, and then lit by the BAI some thirty minutes before the visiting fire crews arrived for BA training. With the fire burning well, it would be topped up with more pallets, each being carried through the doorway and thrown in sending a shower of sparks into the air, the BAI shielding his face as best he could from the radiating heat; the heavy metal and insulated self closing door propped open against closure.

That heavy metal door was to almost take the lives of two BAIs on separate occasions. The events were officially kept secret by the first victim, though privately shared between us fellow BAIs; I’ll share just one with you.

It was a winter dark evening time and the BAI was there early and alone. He entered the fire room and lit the fire; breathing apparatus was never used in these circumstances for practical and procedural reasons.

The flame started to rise and take hold; the fire had a firm grip on the timbers by the time our BAI – a big man – heard the unmistakable loud metallic thud and clang of that great metal door slamming shut and, outside, the locking mechanism snapping into place. For him it was too late to dismantle the fire of fuel, serious burns would be inevitable, he rushed to the door and searched for a handle – if there ever was one under the insulation and thick wire mesh that held it in place we never found it – anyway it’s an irrelevance – he was not going to find it that night! He needed to get out of that fire room, and damn quickly, no good waiting for the arrival of the fire crews, they wouldn’t think of looking in there, literally the last place they would look, by then he would be long dead; having died the most terrifying and slow death by the radiated heat; in the morning it might be that just a few bones and buttons would tell the tale.

Well, fear and an overwhelming desire to get the hell out was coursing through his very being.

There was a way out!

It was through the same hole that those soon to be searing hot flames would be leaving and then it would be impossible – one breath of those hot gases and the lungs would be irretrievably and fatally damaged. He had to act quickly; how he managed to pull himself up to the height of those transom openings above the inner doors even he will not know, how he managed to squeeze his huge frame through that small opening he will never know, and how he managed in the darkness to find the floor some eight feet down and head first he will not know. What he does know is that he is out – alive – safe.

What he achieved would surely be impossible if it were not for those terrifying circumstances in which he had found himself.

Some of what we did, what we saw, taught, discovered and learned is always with us in our minds. We had to know more, experience more and stay longer than those we strived to help improve their chances of survival when wearing BA out there in the world of real fires, that didn’t have sprinklers and controlled ventilation systems when life was threatened.

I hope I’ve given you a taste of some of the honest and sometimes truly frightening tales from the smoke house. This is a true story.

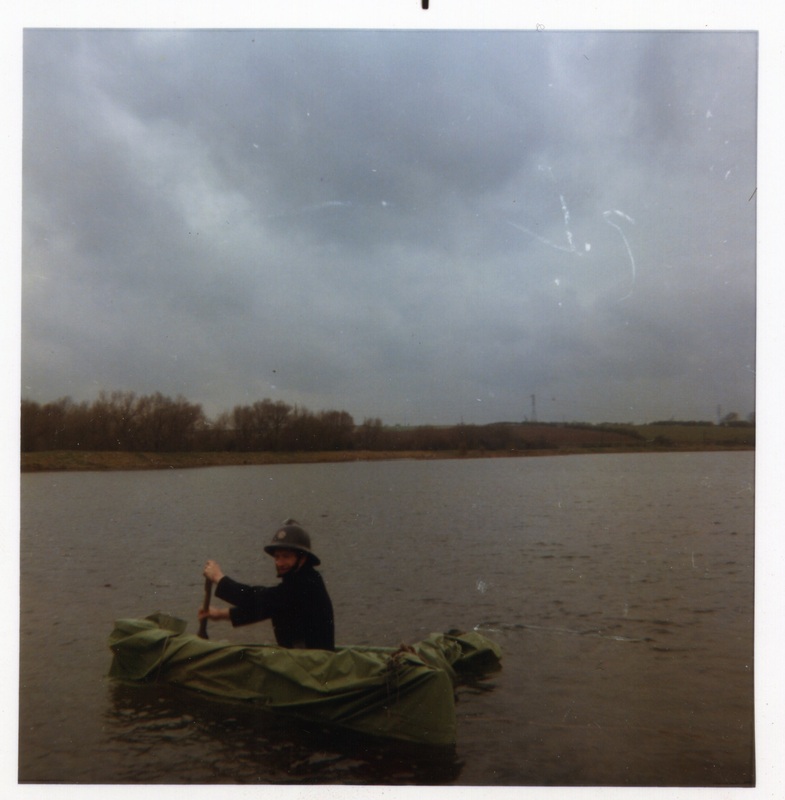

Life jackets? . . . and we called it training !

It was a serious business, indeed, a matter of life and death, we had to trust never to let each other down. . . not to knowingly let each other down anyway.

We were in at the deep end in more ways than one. We were keen, disciplined and enthusiastic but the almost non-existent training and insight we had been given was a pauper's substitute for a properly developed experiential apprenticeship whereby we could have learned from those who were truly skilled and from other’s mistakes.

We were going to have to make some of our own. . . and we did that too.

Firstly we had to find somewhere suitable to carry out our training. When I tell you it was all to do with life jackets you’ll think, “Aha – they’ll need water. Mmm, a swimming pool will do or perhaps a river.” Good, I like your thinking, however for health and safety reasons we must discount the river, or indeed the fine outdoor pool that had been unused over winter – we couldn’t be allowed to use it in case the water was dirty – even if it was perfect for our needs.

“Well, you’ve got lots of swimming pools around, just use one of those,” I hear you suggest.

Excellent idea; and mine too; somewhere clean, with showers, changing facilities, local, secure parking and lockers etc., in fact, ideal. Now try finding one that will let you even look at their pool in full fire kit, (operational fire fighting clothing including boots and other carried equipment), and that’s if they have a vacant slot in their swimming programme, usually completely filled by schools or the public.

With a great deal of hard work, gentle persuasion and compromise we found a place that would help us. We were allowed two fenced off lanes and must ensure that all our gear was thoroughly clean before entering the pool area.

Sorted! All gear to go in the station’s big washing machine and allocated solely to the ‘life jacket course’, which in itself was only a couple of hours long. Life jacket training was to be done whenever the pool was available, even if it occurred weeks prior to the rescue boat course itself.

We had two types of life jacket, one was a bulky full size unit and the other was a lightweight slim waist jacket type that had to be inflated manually by pulling an activation toggle. Well, that little red toggle wasn't always easy to find in good conditions so I reasoned that in full panic mode it would be nigh on impossible so I always chose to wear the ready to use with no thought version. The red toggle was to have other implications too.

Though we covered some theory poolside it was essentially a practical course. Despite having a warm water pool to use we had to pretend otherwise for our 'cold water entry' drill. The intention was to clamp the mouth and nose shut on entering the 'cold' water which hopefully stops you breathing in the river when the your body is shocked to gasp for more air; a natural reflex as you'll all know from your own cold water experiences. Before jumping in the water be sure that the strap on your fire helmet is undone. . . if not, your neck will be, as your body sinks lifeless to the bottom leaving your head floating attached to your fire helmet.

OK, so now we are safely in the water. Test one; can we actually get out again on our own. Test two; can we rescue a colleague. . . just to tow them a short way to the bank and assistance. . . some of which may prove dubiously useful.

There were different ways in which this assistance could be manifested and big Dave, an ex-military man sometimes known as 'Rab', was to demonstrate one method, how to lift me out of the water assisted by the water itself. Easy; take one good strong grip on the life jacket 'handle' and proceed to bounce the floating casualty in the water, pushing them down and pulling up assisted by the lift of the water. Up and down we went, or was it down and up? Then, when the momentum is right, haul them up and on to the bank, or in this case poolside.

'Rab' was a big fellow, ex Royal Navy diver, which is why we'd seconded him to our group; down I went and up I came, then down I went again and up again, at which I began to wonder just how many times I was to be ‘baptised’, then down and only partially up as the strap on the life jacket slipped undone and the hole through which I had put my head earlier shot upwards sounding like jet aircraft engines on afterburners as it passed by my ears taking a shade of skin with it and leaving friction burns behind. My ears cooled mercifully as I sank into the pool and 'Rab' stood with the students on the poolside holding up high in one hand the 'rescued' casualty, one empty life jacket.

Yes, you are right. . . they couldn't stop laughing.

Some mistakes were obvious. . . sometimes only in retrospect mind you, for example, Fire Fighters might have to wear breathing apparatus as well as life jackets; which one do you put on first; The heavy cylinder of breathing apparatus or the light waist coat type life jacket? Answer is Breathing Apparatus; if you do it the other way around the life jacket cannot usefully inflate but might try and squeeze the life out of you!

Now back to those waist coat type life jackets. . . inflated by a small carbon dioxide cylinder activated by a trigger attached to the infamous red toggle. Normally the writer writes history in their own favour, leaving out their own foolishness and mistakes, we shall deviate from that norm here and write a confession. (It's not all my fault mind you as we really should have been trained better ourselves, we were victims of constant appalling management. . . there, I feel a little exonerated and able to continue now.)

We were teaching something of which we knew little ourselves; well, arming the gas cartridge wasn't just a simple matter of screwing in a new cylinder, oh no, the trigger had to be reset first. If you didn't reset the trigger you could pull the toggle until the cows come home and the jacket will never inflate.

I know this from first hand experience as I did it to myself – no wonder I never liked that type of life jacket. Thinking about it now I see it as a design fault; it should have been designed such that a full cartridge and an armed trigger were a pre requisite for the toggle to indicate it was ready for use, and not how it was. . . either badly connected or already a discharged cylinder. Another quick tip while on the subject. . . if a carbon dioxide charged life jacket needed topping up through the wearer's manual inflation tube you'd better make sure you never breathed in !! Instant unconsciousness would be the result, possibly followed by some other catastrophe of which you would remain blissfully unaware. It was a life jacket type I always avoided, though it remained a favourite with the operational fire crews.

What is even worse, I'm ashamed to admit, is I set up a life jacket incorrectly for someone else. Apologies, Nicky. She donned fire kit, breathing apparatus and 'serviced' life jacket, then in she went with a splash at the deep end of the pool. We could see her under the clear water, (I suppose better than dirty river water in the light of this last revelation, eh?) struggling to find that essential and elusive red toggle, all is OK we watching students and 'instructors' see her struggle and her success. . . she finds the toggle and pulls, the look of relief on her face is short lived and turns to puzzlement beyond the clear plastic face mask of the breathing apparatus. Puzzlement turns to exertion and desire. . . to get out of the water. . . and, as she struggled to the pool edge, students looked on with shock and I with a touch of guilt and knowing. Another mistake under the belt, all in the name of training.

We made light of the situation, I mean we wouldn't have let her drown would we, . . . and soon the next student was preparing for the ordeal by mistakes, er, I mean by training..

******************************************

It was a serious business, indeed, a matter of life and death, we had to trust never to let each other down. . . not to knowingly let each other down anyway.

We were in at the deep end in more ways than one. We were keen, disciplined and enthusiastic but the almost non-existent training and insight we had been given was a pauper's substitute for a properly developed experiential apprenticeship whereby we could have learned from those who were truly skilled and from other’s mistakes.

We were going to have to make some of our own. . . and we did that too.

Firstly we had to find somewhere suitable to carry out our training. When I tell you it was all to do with life jackets you’ll think, “Aha – they’ll need water. Mmm, a swimming pool will do or perhaps a river.” Good, I like your thinking, however for health and safety reasons we must discount the river, or indeed the fine outdoor pool that had been unused over winter – we couldn’t be allowed to use it in case the water was dirty – even if it was perfect for our needs.

“Well, you’ve got lots of swimming pools around, just use one of those,” I hear you suggest.

Excellent idea; and mine too; somewhere clean, with showers, changing facilities, local, secure parking and lockers etc., in fact, ideal. Now try finding one that will let you even look at their pool in full fire kit, (operational fire fighting clothing including boots and other carried equipment), and that’s if they have a vacant slot in their swimming programme, usually completely filled by schools or the public.

With a great deal of hard work, gentle persuasion and compromise we found a place that would help us. We were allowed two fenced off lanes and must ensure that all our gear was thoroughly clean before entering the pool area.

Sorted! All gear to go in the station’s big washing machine and allocated solely to the ‘life jacket course’, which in itself was only a couple of hours long. Life jacket training was to be done whenever the pool was available, even if it occurred weeks prior to the rescue boat course itself.

We had two types of life jacket, one was a bulky full size unit and the other was a lightweight slim waist jacket type that had to be inflated manually by pulling an activation toggle. Well, that little red toggle wasn't always easy to find in good conditions so I reasoned that in full panic mode it would be nigh on impossible so I always chose to wear the ready to use with no thought version. The red toggle was to have other implications too.

Though we covered some theory poolside it was essentially a practical course. Despite having a warm water pool to use we had to pretend otherwise for our 'cold water entry' drill. The intention was to clamp the mouth and nose shut on entering the 'cold' water which hopefully stops you breathing in the river when the your body is shocked to gasp for more air; a natural reflex as you'll all know from your own cold water experiences. Before jumping in the water be sure that the strap on your fire helmet is undone. . . if not, your neck will be, as your body sinks lifeless to the bottom leaving your head floating attached to your fire helmet.

OK, so now we are safely in the water. Test one; can we actually get out again on our own. Test two; can we rescue a colleague. . . just to tow them a short way to the bank and assistance. . . some of which may prove dubiously useful.

There were different ways in which this assistance could be manifested and big Dave, an ex-military man sometimes known as 'Rab', was to demonstrate one method, how to lift me out of the water assisted by the water itself. Easy; take one good strong grip on the life jacket 'handle' and proceed to bounce the floating casualty in the water, pushing them down and pulling up assisted by the lift of the water. Up and down we went, or was it down and up? Then, when the momentum is right, haul them up and on to the bank, or in this case poolside.

'Rab' was a big fellow, ex Royal Navy diver, which is why we'd seconded him to our group; down I went and up I came, then down I went again and up again, at which I began to wonder just how many times I was to be ‘baptised’, then down and only partially up as the strap on the life jacket slipped undone and the hole through which I had put my head earlier shot upwards sounding like jet aircraft engines on afterburners as it passed by my ears taking a shade of skin with it and leaving friction burns behind. My ears cooled mercifully as I sank into the pool and 'Rab' stood with the students on the poolside holding up high in one hand the 'rescued' casualty, one empty life jacket.

Yes, you are right. . . they couldn't stop laughing.

Some mistakes were obvious. . . sometimes only in retrospect mind you, for example, Fire Fighters might have to wear breathing apparatus as well as life jackets; which one do you put on first; The heavy cylinder of breathing apparatus or the light waist coat type life jacket? Answer is Breathing Apparatus; if you do it the other way around the life jacket cannot usefully inflate but might try and squeeze the life out of you!

Now back to those waist coat type life jackets. . . inflated by a small carbon dioxide cylinder activated by a trigger attached to the infamous red toggle. Normally the writer writes history in their own favour, leaving out their own foolishness and mistakes, we shall deviate from that norm here and write a confession. (It's not all my fault mind you as we really should have been trained better ourselves, we were victims of constant appalling management. . . there, I feel a little exonerated and able to continue now.)

We were teaching something of which we knew little ourselves; well, arming the gas cartridge wasn't just a simple matter of screwing in a new cylinder, oh no, the trigger had to be reset first. If you didn't reset the trigger you could pull the toggle until the cows come home and the jacket will never inflate.

I know this from first hand experience as I did it to myself – no wonder I never liked that type of life jacket. Thinking about it now I see it as a design fault; it should have been designed such that a full cartridge and an armed trigger were a pre requisite for the toggle to indicate it was ready for use, and not how it was. . . either badly connected or already a discharged cylinder. Another quick tip while on the subject. . . if a carbon dioxide charged life jacket needed topping up through the wearer's manual inflation tube you'd better make sure you never breathed in !! Instant unconsciousness would be the result, possibly followed by some other catastrophe of which you would remain blissfully unaware. It was a life jacket type I always avoided, though it remained a favourite with the operational fire crews.

What is even worse, I'm ashamed to admit, is I set up a life jacket incorrectly for someone else. Apologies, Nicky. She donned fire kit, breathing apparatus and 'serviced' life jacket, then in she went with a splash at the deep end of the pool. We could see her under the clear water, (I suppose better than dirty river water in the light of this last revelation, eh?) struggling to find that essential and elusive red toggle, all is OK we watching students and 'instructors' see her struggle and her success. . . she finds the toggle and pulls, the look of relief on her face is short lived and turns to puzzlement beyond the clear plastic face mask of the breathing apparatus. Puzzlement turns to exertion and desire. . . to get out of the water. . . and, as she struggled to the pool edge, students looked on with shock and I with a touch of guilt and knowing. Another mistake under the belt, all in the name of training.

We made light of the situation, I mean we wouldn't have let her drown would we, . . . and soon the next student was preparing for the ordeal by mistakes, er, I mean by training..

******************************************

Cambridge Fire Station, a story and pictures.

***********

***********

South Division control room.

South Division control room.

The Silent Bells.

Written in 1985 at Cambridge Fire Station, the way of life was much different then, you’ll understand, and long past now, along with the lives of some of the men who were there.

The heavy thud and clonk of the great yard gates broke the night silence as they were closed and locked against the unwelcome from outside. It was followed by the sound of hurried footsteps as the duty-man returned, running to the rear door, also disturbing the quietness. It was dark outside, but inside, dim night lights burned throughout. In the background were the whirring sounds of a nearby office block’s air conditioning system and the seemingly ceaseless passing of motor vehicles on the roadway outside, occasionally the imprisoned stray dog in the police pound next door would bark in fear or boredom.

The main reason for their presence in the building had not come to fruition that evening, but, there were several hours to pass before this shift would end, and they all knew, that as uneventful seconds, minutes and hours ticked by, they were nearer to the inevitable call to action.

It was a strenuous lifestyle that demanded flexibility and discipline from the men that led it. There could be no delay at mealtimes, no slow savouring of the meals prepared high up in the top floor kitchen, as every uneventful second that their meals lay before them meant they were closer to the soft click of the relay that brought the station’s lights bursting into life and the booming sonic warning that foretold of someone’s distress. An alarm that would bring men running from their meal or from duties all over the station, with hearts beating faster and adrenalin flowing they would climb aboard those familiar Red Lorries. The Officer in Charge would run to join them with scribbled details from the control room, shouting the address to the driver and details to the crew who by then were already partly into their fire fighting gear. The chains of the electrically operated doors would be rattling and clanking along the ceiling and already the powerful sound of big diesel engines and the flashing blue lights would charge the air. From the nines bells ringing in control to assistance mobile on the road was a matter of 40 seconds, you’ll not beat that in the future, because the way of life is changing.

So far that night it had been quiet, the crews had left the station only for routine testing of water supplies and a minor oil spillage on the highway, but they knew that at any second they could be called to respond. Sometimes they would be asked to risk their lives; sadly sometimes that fatal forfeit must be paid. No one thought of the job like that; no different from millions of motorists who think an accident will never happen to them despite the appalling annual road death figures. However, experience reveals that at any second fate can show its hand, and fate seemed pretty liberal with its handouts.

It was gone midnight, and a main light burned in the kitchen where a large kettle gently steamed on a low gas and someone washed and dried a few cups before they settled down to rest. Unlike the youngsters, the older men no longer waited eagerly for the bells to go down, they knew it would happen soon enough, in fact, any second soon enough.

The dark hours slipped away silently; the world was at peace. As dawn light probed the surrounding buildings, dismissing the shadows for another day, so too were the men of White watch preparing for their dismissal at nine o’clock. The fire engines were checked for cleanliness and the kitchen tidied, some men were still eating breakfast and trivial banter, only funny to men who knew each other well, flowed freely about the room. Still the bells were silent, which was good news for the City folk, who by now were long up and thronging the streets about their business but fire seemed predestined and it was fire these men had joined to fight.

Whenever the doorbell or telephone rang it could mean action, but almost invariably it signified nothing, they were used to this. No chances were ever taken; response to a call was always the same, immediate and caring, impartiality a byword.

So many were the stories told by the firemen over a tea break or changing in the locker room; tragedies, comedies, and sometimes a playful exaggeration. From a crowded street, where two children died while people cursed for the Fire Brigade – that no one had thought to call, to the man with a pet Gerbil stuck in a vacuum cleaner pipe, or the boy with a tin on his head, or worse, one down the funnel of an old railway steam engine. From cold stormy winter nights to baking droughts, dogs down wells, drowning fish and people stuck in toilets, they would each tell their story.

Later that day a warm rain spattered on the concrete drill yard outside as the oncoming White watch gathered for the start of their second night. Time too had passed without excitement for the day watch. With an average of ten calls a day it was rare to have long stints of inaction, and as time ticked by the likelihood of fire grew imminent. Large fires would usually manifest every few months, but it seemed many years since the City had seen one, surely it was on the cards, and perhaps it would be this night.

On route to fires the men would be looking for smoke in the distance and when nearer for water supplies should they be needed; they liked it when someone stood in the street and waved directions, especially if the call was to a modern, ‘labyrinth’, estate where the numbering system seemed to have been done as a cruel joke, or in a road where common numbers had been discarded for grand and self important house names, difficult in the dark and rain at speed. Sometimes men would complain bitterly but this was not negative, no, just a measure of their conviction and willingness to arrive quickly and do their duty for those who had made a cry for help, and after all, who paid their wages.